South Korea’s annual college entrance exam should serve as reevaluation of standardized curriculum

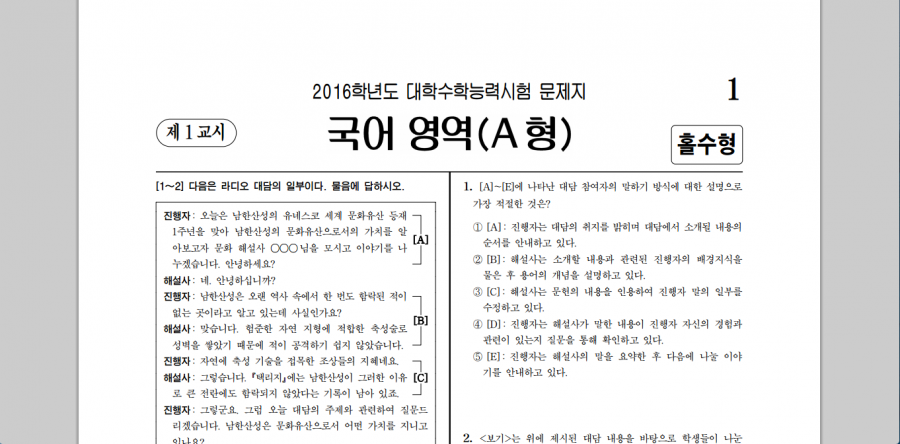

Photo courtesy of www.naver.com. A released test form for the 2015 CSAT administered in South Korea for high school third-year students.

November 30, 2015

November 12 was especially special for me this year.

It was the day of South Korea’s administration of the annual college entrance exam, or suneung, as it is referred to in the nation. Officially named the College Scholastic Aptitude Test (CSAT), the CSAT is a government-sponsored exam that all high school third-years (South Korea has a three-year high school system) are required to take in order to qualify as an applicant for nation’s most renowned universities.

Having been a resident of Seoul for ten years prior to my stay in the United States, I felt a strange tinge of anxiety and pressure as I started that special day in November. At first, I could not determine where the feeling of discomfort was coming from. I could feel my mouth drying, heart beating and hands constantly fidgeting around.

As I scrolled through pictures of students and parents updated on the South Korean news, I finally realized that the source of anxiety was originating from the hypothetical question: What if I was the one there?

If I were in South Korea, I would have been the one packing my backpack and reviewing one more English word before heading outside to the cold November air. I would have been the one receiving the enthusiastic cheer of underclassmen and their small good-luck charms of South Korean snacks as I entered the school. I would have been the one, who, with the hundreds of thousands of other 97s, experiencing the culmination of my 12 years of academics with a single exam. Visualizing myself in the environment, I realized that I was not only feeling anxiety, but also fear.

The CSAT in South Korea is the epitome of standardization in academics. The exam, which is supervised, organized and distributed by the Korea Institute of Curriculum and Evaluation (KICE), is the final point of every high schooler’s public education and a powerful factor in his or her admission into the nation’s top schools, the most renowned three being Korea, Seoul and Yonsei Universities, or “SKY.”

The CSAT is the fastest way, and often the only way, in which a student can gain the lucky golden ticket into the selected schools, unless he or she receives an early admission. This may serve as a reason why the nation has been receiving international attention for its incredible, almost obsessive, attention to academics and numerical scores.

Some say that standardized exam is the most objective way to evaluate students’ academic achievements. That may be true in a general sense. Yes, standardized exams are clear-cut. Every student takes the same test, and they receive scores that directly represent their abilities.

However, the simple assertion fails to look closely at the dismal aftermath of standardized exams. Numerous, if not all, students in South Korea attend after-school hakwons, or private academic programs and institutions, to gain greater and faster access to school curriculum. Even when I was in South Korea, which was approximately eight years ago, it seemed acceptable to let students study materials that were one to two years ahead of their academic standards set by schools.

It is the widespread mindset of “the faster you are exposed to the materials, the faster you will learn” that elevates the hakwon industry into one of the most lucrative businesses in South Korea, one that has almost become a required system in which a student not taking a course at a hakwon would be considered an outlier.

The simple and efficient method of standardization is, in ideal, the perfect way to promote impartiality in a world that has become greatly polarized, stratified and biased over the past decades. However, we must recognize that the act of strict standardization rather perpetuates the exactly opposite effect of its intent—it promotes an environment of greater competition and consumption in order to get the scores that the students need to succeed in life and move up in their socioeconomic ladder. And, if the only path for prosperity is by succeeding on a single test, it is unfathomable how far the society will go to earn that goal.

I checked my clock and converted the time into that in South Korea. I realized that the test had ended five minutes ago. I sat back onto my chair and imagined how I would have felt. It would have been bittersweet, definitely relieving, maybe anxious and, strangely, sad. As I thought of myself walking across the vast soccer field from the school building to its entrance, I felt a strange tinge of depression that everything went by so quickly, too quickly—those eight hours could never be the representation of the 18 years of relentless effort and passion I’ve put into my life.

The issue of standardization does not lie on its essential concept. It is the aftermath of standardization that is concerning; if students are ultimately to be categorized by their scores, the center of the problem should be directed to schools, in which they are created to promote a community of thought and discussion, not numbers and competition.