Speaking up about trigger warnings

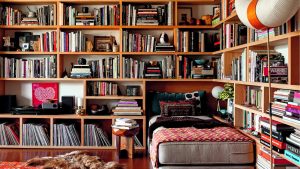

According to the New York Times, at the University of California, Santa Barbara, the student government recommended that professors provide trigger warnings for sensitive topics. Creative Commons photo courtesy of Flickr user John Morgan.

February 9, 2017

We regularly hear about suicide, sexual assault, death, and discriminatory crimes on the news and on social media. Last year, we witnessed mass violence like the shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando and those on police officers in Dallas and Baton Rouge. Scrolling through Facebook, one sees stories that start like this: “Rosie Ayliffe’s daughter was stabbed to death last year.” Though we’re rarely warned before seeing this content online, some have taken to using trigger warnings for online pictures, Tumblr posts, books, poems, etc. involving any type of sensitive content such as violence, gender inequality, racial discrimination, or sexuality. For example, a poem about a traumatic event on Tumblr could have the caption: “Trigger warning: sexual assault.”

Trigger warnings were originally intended to warn soldiers with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) of visual, auditory or written depictions of events that would induce painful mental and physical symptoms. For example, a movie with a gruesome combat scene could remind the viewer of a stressful, traumatic memory from the battlefield. They can also appear on books such as Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, and Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway. One anonymous Jefferson student spoke about her experience as someone who has PTSD.

“[Being triggered] is basically re-experiencing a traumatic event,” she said. “I need [trigger warnings] for things that are related to mental illness and things that cause traumatic events. Like when somebody’s posting on TJ Vents [a Facebook page where students post anonymously] that they’re suicidal and that they’re going to die or that they already tried to kill themselves and that they failed, those are things that will trigger me. My heart will start to race really fast, I will start to hyperventilate, I’ll get really, really sweaty and I could get a flashback, which causes unbearable pain due to the rise of stress hormones in my body. It’s not because I’m a sensitive person or a weak person, it’s because I’m probably having some sort of flashback to events that happened in the past.”

She has noticed that the original intent for trigger warnings has become lost for many people.

“The only people that actually have a trigger [are people] with PTSD,” she said. “A lot of people misuse the term and think that trigger means that somebody’s upset or that they disagree with an opinion but that’s not actually true. Trigger warnings are not for controversial subject matter, but are for serious topics, like suicide, rape, human right’s violations, [etc].”

Senior Alex Prosak expressed confusion over the amount of trigger warnings that students at some colleges see on literature.

“My sister goes to Brown,” he said. “Her professor gives her things and [they’re] filled with trigger warnings. She’s shown me trigger warnings of mentions of alcohol. If they read a story about war, there’ll be like trigger warnings about graphic scenes or like graphic explanations. I think it’s kind of gotten out of hand.”

Some feel that these are accommodating for any student who may need those trigger warnings, but others feel that they assume students’ needs and overgeneralize. Many colleges have systems in place for students to speak with professors about their specific needs concerning PTSD, allowing their professor to consult them before a lecture involving potential triggers. Some universities and colleges also have safe spaces for survivors of sexual assault and the LGBT community that many colleges offer. Senior Jack Boyle feels that they’re ineffective.

“College should ultimately be an experience to prepare you for that, to prepare you for anything that comes at you,” Boyle said. “And I think trigger warnings are really failing on that count.”

However, according to our anonymous source, trigger warnings are like television ratings and just as necessary.

“We give warnings to parents so they can make sure their children don’t watch when sensitive subject matter is going to come on television,” she said. “We rate movies based on their violence factors. We should put warnings on things saying ‘warning: violent/sensitive subject matter.’ ”

Though she and Prosak disagree on the effectiveness of trigger warnings, both feel that trigger warnings are sometimes used unnecessarily or misunderstood.

“At some point there’s no real line to draw as to what should be given a warning and what shouldn’t, so what ends up happening is you just get warnings for basically everything,” Prosak said.

According to Boyle, trigger warnings could be used for violence in literature or television, but they’re sometimes unnecessary.

“I get it when [trigger warnings are] for things that are super disturbing or just generally recognized as graphic, like really gruesome, like war scenes or something like that, that makes a little sense,” he said. “But if it’s just language or something like that, then it’s more just putting people in a bubble and then it doesn’t really prepare them for the real world.”

Prosak’s research on PTSD has led to his view that trigger warnings disadvantage the same people they’re meant to help because they encourage avoidance.

“I read a study about soldiers with PTSD and one of the ways they actually helped to overcome their PTSD is [by] slowly getting more exposed to things that could trigger episodes. If you’re just shielding yourself from any sort of exposure whatsoever, the day that some event that comes that could trigger an episode, it’ll be really bad.”

But according to the anonymous student, trigger warnings don’t encourage avoidance or insulate people with PTSD. Rather, they allow them to choose whether they are ready to face a potential trigger.

“It’s not so they can run and hide, it’s so they can prepare themselves,” she said. “They’re going to say, ‘Okay, there’s a sensitive subject on whatever’–it’s in class, maybe—‘[So] I’m going to do some grounding exercises, I’m going to sit here ad take some deep breaths, I’m going to do some diaphragmatic breathing or whatever and I’m going to focus on my happy place focus on my safe place in my head and try to calm myself down and I’m going to do things that will prevent negative things from happening.’ ”

But according to Prosak, outside of the academic world, triggers could occur without warning.

“If something that triggers an episode would be like seeing a sex scene on TV, things like that are bound to happen, so if you just try to shut yourself out when you’re young, when you get to the real world, it’s gonna be a lot harder,” Prosak said. I think that even if it takes a while and you have to do it gradually, talking about it and just sort of trying to heal yourself psychologically, trigger warnings won’t really help that.”

The anonymous source used to think along those same lines, believing that she could desensitize herself to her triggers by facing them repeatedly. But, according to her, this method, exposure therapy, is disastrous.

“It’s just a bunch of undue suffering that leads to absolutely nowhere,” she said. “I went through that where I thought that I would just be a strong person and I would just tough it out and I could just tell myself not to be afraid of it and not to think about it. But I’ve been told by a bunch of mental health professionals that that’s not the case. No matter how strong you, no matter how much they try to outthink, it you can’t fix PTSD by thinking.”

Therefore, while Anonymous knows that triggers are present everywhere without being labeled as so, she disagrees that trigger warnings prevent healing.

“I’m challenging myself every day. I deal with the real world on a daily basis,” she said. “I’m exposed to all sorts of triggers all the time. It’s not like I live my life in fear of all these little things at all. I feel very empowered and I feel like I’m not acting like some victim, but rather like the hero of my story.”