Voice to the Victims

Victims of sexual harassment use experiences as force for change

April 29, 2017

Their interactions began with an expression of concern.

When Jess found out about Aidan’s mental illness, she made a care package for him that included a list of coping skills. Jess chose to remain anonymous because she feared retaliation from sexual predators, bullies and the administration for sharing the specifics of her story; she was just one of the victims that was harassed by the alleged perpetrator Aidan, who will remain anonymous because of his status as a minor.

“[Aidan] seemed really standoffish at first,” Jess said. “Later in the year, a friend told me that he was bothering her, like asking her questions about being a girl, because he was transgender, and that she didn’t want to answer them because they made her uncomfortable. So I started talking to him, and I offered my friendship.”

Within two hours, Aidan had already begun asking her for sexual favors through manipulation, bringing up personal issues such as mental illness and gender identity, issues that resonated with Jess.

“He didn’t even know me, who I really was, but he talked about things that actually had an impact on me. He talked about being abused, he talked about having mental illness, he talked about being transgender and he talked about being suicidal. Those are all four things that I have a lot of personal connection with, and I don’t know how he knew how to talk about those things and get my guard down.”

In a study conducted by the American Association of University Women, 20% of high school students reported being sexually harassed online through “unwelcome sexual comments, jokes, or pictures or having someone post them about or of you.” In this particular situation, Aidan acted under the guise of one exploring his identity and lied about abusive parents in order to harass his victims and gain his victims’ confidence.

“He immediately tried to manipulate me by acting like he was this tiny little guy who could never hurt me,” Jess said. “He tried to make claims that he was severely mentally ill and he was transgender, and that he would never be able to know who he really was if I didn’t let him touch me and do sexual favors for him. I told him that the girl he sexually harassed had every right to report it to the administration. He tried to manipulate me into not reporting him; he told me that his parents would beat the shit out of him if I told on him or anybody else told on him.”

Jess immediately responded to his situation by urging him to call child protective services. However, he soon confessed that his story was untrue.

“I caught him in a lie,” Jess said. “He admitted he lied.”

The stories that Aidan allegedly fabricated and the tactics that he used were not isolated. Senior Hannah Collins said that he asked personal questions when discussing his gender expression. As a transgender co-president of the Gay Straight Alliance (GSA), their connection with the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community was a starting point for these encounters, which eventually escalated into questions that became “very borderline sexually explicit,” Collins said.

“[It] first seemed as if he were asking for advice dealing with [being] trans,” Collins said. “This is something I’m used to; I position myself [so that] I’m available to the TJ community, if anyone has questions about being LGBT, and if anyone feels a certain way and wants to talk with someone to share that experience, so this wasn’t anything out of the blue. Over time, the conversation became awkward and more and more creepy, and he just wouldn’t lay off on it.”

Initial conversations concerned body image, particularly Collins’ feelings about body dysphoria, which is distress or anxiety caused by feeling as though one is a different gender than what they were assigned at birth.

“At first I obliged his questions because these are the questions that trans people often have, but they did eventually cross a line,” Collins said.

The questions began to focus more on Collins’s relationship with her own body; they said that the student seemed too eager to learn personal details about Collins’s sexual identity.

“Something seemed off about his tone,” Collins said. “I said no several times. Eventually, I turned him down enough that he kept messaging me and I just stopped responding.”

Before they cut off communication, he made continuous and unwanted attempts to meet up with Collins in isolated and empty locations.

“He wanted to meet me in the Weyanoke trailers,” Collins said. “He chose locations in the school that are more empty, locations in the school that teachers are not around, or students are not around.”

Attempting to meet in a secluded location, in addition to questioning girls about their bodies and requesting suggestive videos, were common advances that Aidan allegedly used to sexually harass numerous victims.

“There was a deliberate pattern; he was going to execute actions a certain way by saying certain things,” junior Mariam Khan, who also received uncomfortable messages from Aidan, said. “He asked [his victims] to sit with him at lunch. He would find excuses to make them feel uncomfortable.”

This kind of uncomfortable behavior first began gaining public attention on social media when an anonymous user detailed Aidan’s behavior in a submission to the TJ Vents Facebook page.

“[T]ypically the invitation to eat together occurs over messenger and the individual says things like how he shouldn’t be rejected because he has depression, how you should eat lunch with him in a less populated place because he is not comfortable around other people,” the post continued.

https://www.facebook.com/tjvents/posts/1347568885281720

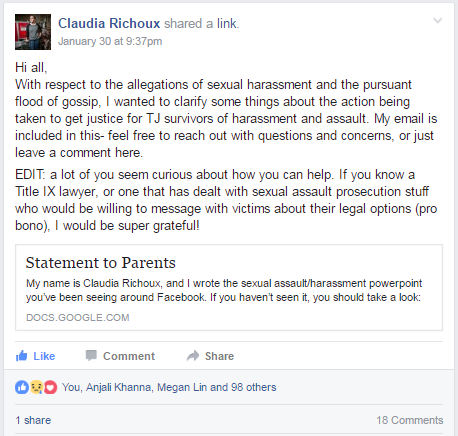

On Jan. 26, Claudia Richoux, class of 2016, increased awareness of the issue by authoring a TJ Vents post. In her post, she responded to the earlier anonymous submission on TJ Vents in attempt to make the community aware of a harasser’s tactics and activities.

“I participated in an extracurricular with this individual last year, and he harassed me, asking for sexual favors and romantic attention on the pretense of my sexuality and that I might be able to function as a mentor for someone who was struggling with his identity,” Richoux wrote. “Fortunately, he has since stopped targeting me, and I didn’t even catch a glimpse of the perversities this student has subjected his other victims to.”

https://www.facebook.com/tjvents/posts/1351565878215354

With her post in the TJHSST Alumni Facebook Group, Richoux attached a presentation on rights that victims are entitled to under Title IX, further publicizing her message by including links and letters. As of Apr. 29, Richoux’s post in the Alumni group has received 100 reactions and 41 comments.

“I was so excited for the reaction [I received for these posts],” Richoux said. “Several leaders in the TJ parent/alumni community reached out to help me spread the word among parents. Many lawyers and journalists sent me emails offering free legal counsel, or to write stories in several major newspapers about the harassment problem at TJ. Many students reached out to say thanks, and that they were going to be actively fighting harassment in the future.”

According to Richoux, as of Feb. 19, approximately 30 people contacted her regarding sexual harassment cases, including at least 18 victims targeted by one alleged perpetrator and ten concerning unrelated cases.

“Together, we compiled things and we went to the administration altogether,” Khan said. “With more people, the case becomes bigger than just if one person went. Because it shows repetition and it wasn’t just one mistake.”

Administrative Actions

According to Jess, victims of sexual harassment first began filing reports to the administration around the end of the 2015-2016 school year, with at least three victims coming forward to report their harassment cases.

“Dr. [Tinell] Priddy was handling the investigation up until the end of last year, and as far as I could tell, she was doing a fantastic job,” Richoux said. However, Richoux felt dissatisfied with how the administration dealt with harassment cases during the 2016-2017 school year.

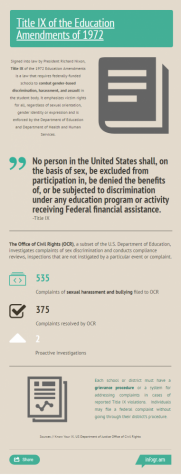

According to Richoux, “There were a lot of violations of Title IX in dealing with the victims.” Nationwide in the 2015-2016 fiscal year, 536 Title IX complaints were filed to the US Department of Education Office of Civil Rights (OCR) pertaining sexual harassment and bullying.

“There’s a huge disparity between the number of victims who reported [Aidan] to administration and how many times he was suspended,” Richoux said.

After allegations of the student’s behavior reached the administration’s ears, Principal Evan Glazer wrote a school-wide email on Feb. 2 to publicly address the student body regarding sexual harassment. “One of the greatest strengths of our community is the respectful and positive relationships our students have with one another,” Glazer wrote. “When allegations arise of a student violating these responsibilities, or another student’s rights, the school administration takes such cases seriously.”

Concerned about the safety and well-being of the student body, Glazer, along with other members of the administration, representatives from the Office of Safety and Wellness, and the support staff at Jefferson, invited the student body to attend a town hall meeting on Feb. 13 in the Lecture Hall. The administration provided an open forum for discussion in order to have a conversation about safety concerns with sexual harassment, including the administration’s limitations and actions in dealing with sexual harassment cases.

“The administration felt that it would be important to help students understand the procedure we use to address sexual harassment, as well as remind students that it’s important to report, as well as help students understand what the school can and cannot do about concerns brought forward,” Glazer said.

“Ultimately, every student has a right to a public education, even if they have poor character, have bad intentions outside of school, or make people feel uncomfortable through their interactions,” Glazer said.

In addition, public school guidelines restrict the domain of offense to school grounds. As a result, harassment that occurs outside the domain of the school does not break a school rule. Nevertheless, the school will still aim to provide support services to students and parents involved.

“If the harassment occurs outside the domain of the school, such as online in the evening… the school’s responsibility is to focus on the safety of the student impacted using strategies we described,” Glazer said. “The school also contacts the parents of the students’ involved because it’s the parents’ responsibility to monitor online behavior at home.”

The restrictions placed on what the school can and cannot do about online harassment is a point of concern for victims of Aidan’s actions.

“Our school is not as safe of an environment as I previously thought it was,” Jess said.

In addition, when “harassing behaviors go unchecked, people will learn that harassment is okay, and then harassment is more likely to take place at school,” Richoux said. Online harassment can make victims “feel unsafe at school, which is an impediment to their learning.”

Glazer and Gravitte recognize that a confidential system for investigating harassment cases can increase students’ frustration concerning the repercussions of a reported case.

“Students feel there’s not enough being done because we hold the records confidential,” Glazer said. “I think that students would have some more assurance if they knew exactly what the consequences are of the student when something happens.”

However, the school is legally prohibited from disclosing the contents of these consequences and files. “We’re required by law to keep that confidential,” Glazer said. “What the students don’t receive is a transcript of the due process that occurs with all the students that are interviewed. The closest thing we can say is, here’s SR&R, you can draw your own inference of what you think the consequence should be.”

FCPS Guidelines for Offenses

According to FCPS Title IX Coordinator Kevin Sills, consequences for perpetrators may include restorative justice and intervention techniques, but vary depending on a case’s circumstances and the number of offenses committed.

While restorative justice is usually the first approach that administrators use when addressing a confirmed perpetrator, they may also contact the Hearings Office for more serious or repeated offenses.

“The Hearings Office administers student discipline,” Sills said. “If there is unwanted touching, so somebody in the hallway or in a locker room or wherever it is there is unwanted touching, we would have the school investigate it and if there’s a determination that there’s a suspension that’s appropriate, or moving a student to an alternate school, the school [would] work with the folks at Gatehouse to determine the appropriate level of penalties.”

“In those kinds of situations…it’s incumbent on the school to take the appropriate next steps,” Sills said. “We’ll provide them the guidelines and resources, but as good as Karin [Rodriguez] is or the rest of my staff is, there are 200 schools. We rely on the schools to put that framework into place and to effectuate it.”

The framework and its effectiveness is what can often come into question by victims who feel that not enough severe punishment is being enacted by the school. According to Becca, the system of repercussions should be extended in order to more effectively address the severity of the harassment that occurred.

“I think the layout of the consequences, [including] suspension, restorative justice, modified schedules, etc., is good,” Becca said. Becca is a victim who chose to remain anonymous because she shared personal information in her statements that she is not willing to share publicly. “For cases of sexual harassment, I think that these same consequences should be more severe: for example, longer suspension. Of course, this should also be decided at a case by case basis.”

“The safety of all students is paramount,” Collins said. “The school should have made efforts to warn students. My biggest concern was never that he would do it again to me, but that he would find another target that did not know his patterns of abuse. I don’t want any other student to go through what I went through.”

When Collins and others reported their case to the school together, they recall encountering procedures and regulations that increased their feeling of discontent.

“When we presented together, they almost got indignant that ‘Oh, you guys are sharing information with each other,’ ‘We need to make sure everything is right,’ ‘We trust you, but we need to make sure no one’s making this up, or no one’s just joining on the bandwagon because they’ve got an ax to grind against the perpetrator,’ ” Collins said. “There was very much this sense of ‘Oh, we can’t really help you do things the right way’ or ‘We can’t help you because yours doesn’t fall under the domain of sexual harassment,’ even though it was clear there was a pattern there were repeated attempts of sexual harassment.’”

During an investigation process, student accounts as well as perpetrator repercussions are kept confidential from the rest of the school. This perceived lack of transparency and action can prompt victims to question the administration’s role.

Although the administration is forbidden from revealing the consequences of a report, they continue to strive for a deeper sense of trust between the students and the administrative staff.

“We want students to know that although they’ll never find out what discipline will be given to the offenders, that you should rest assured that it’s happening,” Gravitte said.

Victims feel not enough is being done

For her case, Becca feels that the “three to five days suspension and the other consequences clearly did not do justice.”

For Becca, the most important result of the lack of severity and justice in consequence was its inability to prevent Aidan from repeatedly harassing more girls.

In the spring of 2016, the Aidan approached Becca as one curious about his gender identity. “I used to be very active [on TJ Vents] in writing comments and offering my own advice or condolences,” Becca said. “One day, I saw this anonymous post about this ‘girl’ who expressed insecurities about her breast size, so I was like ‘Oh, I also do not have very large breasts, so I was trying to offer my advice about self-esteem and stuff like that. One day, this person approached me saying hey, I’m also a ‘girl,’ who wrote this post about feeling insecure about my bra size, so can we just chat more about that?”

Becca agreed to answer his questions, messaging back and forth over the course of a month. In the midst of offering suggestions and guidance, Becca began to feel uncomfortable when the student began probing Becca about her own breasts and size.

“They started pressing me with questions such as, ‘Can I go and feel your breasts, cause I want to know what my boobs could become,’ and messed up stuff like that,” Becca said. “And I repeatedly and firmly expressed my discontent.”

However, he continued to press Becca for sexual favors, ignoring her right to clear and consensual compliance. Becca eventually found herself being coerced and pressured by the perpetrator into complying with his requests.

“[Aidan] did not respect my wishes; [he] didn’t respect that I did not want to do this,” Becca said. “He insisted that this was the only thing that would make him happy, this was the only way to solve the problem. Even after I said no, he kept on pressing, and I kept on messaging him back and forth. And eventually, I was kind of [worn] down, so I was like, ‘Fine, let’s just meet here.’”

Sexual coercion, defined on the Office of Women’s Health’s (OWH) website as “unwanted sexual activity that happens after someone is pressured, tricked, or forced in a nonphysical way,” was used by Aidan in order to wear Becca down. According to the OWH, sexual coercion falls under sexual assault, which is verbal or visual harassment, contact or attention to which one party does not explicitly and fully provide their consent.

“The baseline for consent is unambiguous and informed discussion on where everyone’s boundaries are,” FCPS Title IX Coordinator Kevin Sills said. “The importance of consent is that everybody enters into the situation with the understanding that they were a full and agreeing participant. On one level it’s important so that there’s no misunderstanding, to have the full understanding of what you’re comfortable with. On a broader less emotional aspect of it, I think it’s important so you know how to move forward.”

According to Becca, the perpetrator did not understand the significance of freely-given consent. He continued to use his situation to intimidate her into unwanted sexual contact.

“He even tried to convince me that breasts do not count as private parts, so they clearly did not have the full understanding of the gravity of the situation and how wrong their actions were,” Becca said.

At the time of her interactions, stress from school, as well as concerns about the stigma surrounding harassment, prevented her from reaching out for help.

“I didn’t want to be blamed because of his actions, so that prevented me from reaching out to my friends,” Becca said. “I even had one of my male friends say to me, ‘This was awful, this was terrible, but this is kind of your fault. You shouldn’t have believed this.’ And yes, I do believe that I could’ve been more careful in this situation if I’d known these red flags. I could’ve done more for myself to protect myself, but it’s not my fault that this happened to me because it was him who reached out to me, him who created false accounts to lure me and other girls into doing this. It was all him.”

After conversations with supportive friends, Becca contacted the administration to report Aidan’s actions and to receive support.

“I’m so glad I did,” Becca said. “[My friends] convinced me to talk and reach out to the administration, talk to counselors about this and then from there, I think that’s where administration took over in terms discipline, not only discipline, but also possibly counseling.”

“When I [first] brought [my situation] up to counselors and administration, we never really fully sat down and decided between whether this case was harassment of assault,” Becca said. “I think they recorded it as harassment; I don’t know why we didn’t realize sooner that this was assault. Part of me, in the back of my head, when I labeled it just as harassment, I thought that it was still my fault, even though I knew that coercion was not consent, or that manipulation was not consent either.”

“I never imagined that I would be a victim of sexual assault, I would have fears of like, what if I go to college and I’m walking home in a scary alley and then all of a sudden boom, I get raped, I’ve always had those fears but I never really realised how they come in different forms like this, and I still didn’t realize that [my situation] was assault until yesterday [Feb. 26], which is kind of scary,” Becca said. “I just want people to know that these issues still exist very much, and that we need to do all we can to fight against it.”

The ambiguous nature of Becca’s experience made it harder for her to categorize and for her to stop blaming herself for Aidan’s actions. Because Becca didn’t know until recently that the police investigated offenses separately from the school, and that the police, rather than the administration, determined whether an action was a crime, she didn’t think it was her responsibility to contact the police herself.

Finally coming forward about a harassment or assault case and seeking appropriate resources can be difficult. According to the Maryland Coalition Against Sexual Assault (MCASA), only 15.8 to 35 percent of sexual assaults are reported to the police. When an offender is an intimate partner or former intimate partner, only 25 percent of sexual assaults are reported to the police. When an offender is a stranger, 46 to 66 percent of sexual assaults are reported. Encouraging victims to make that step and present their case to the administration is an important aspect of dealing with these situations.

“When you hear that somebody has been sexually harassed, it’s up to you to try to convince the victim to do something about it, to convince them to go to the administration,” Jess said. “You need to offer to go to the administration with them, to get the conversation started until they’re ready to speak up for themselves. There’s so much people can do. They can value that person’s feelings and not victim-blame.”

“I ask them to be caring and sensitive and understanding about the situation,” Becca said. “If you are having a hard time seeing why it’s the perpetrator’s fault and not the victim’s fault for whatever the scenario is, you can go online and Google definitions of assault, you can educate yourself, talk to some of our resources here [at Jefferson].”

Encouragement from friends and trusted individuals can ease the process of contacting counselors and other members of the administration. On Jan.18, junior Hannah Han, a victim of harassment during her sophomore year, joined that group of individuals as an encouraging voice for others who had experienced similar situations. The Humans of TJ Facebook page published her quotes in which she acknowledged her peers’ role and urged people to reach out to others when in difficult times or positions.

“My experience was a pretty obvious one to share, because I think it would help many other people in my situation, not just in a sexual harassment situation, but people going through hard times,” Han said. “I know if you have a mental illness for example, or if you’re struggling through a situation, you don’t want to bother other people; you want to keep it to yourself. And you think that dealing with it alone would be better than telling a friend, but I just really wanted, from my own experience, to advise people to reach out. Like I said in that post, going through a hard time with someone else is so much better than doing it alone.”

“I would never had guessed that it happened right here at TJ until I read that post, and I think that affected a lot of other people,” Khan said. “After I reached out to [Han], we all formed a group of people affected by the perpetrator’s actions.”

Moving Forward

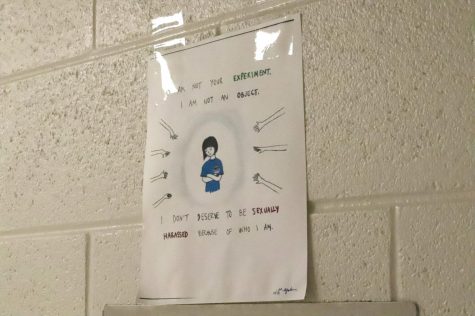

As a result of an increase in student interest, the administration has worked to create an action plan for reform; Glazer has communicated with students to collect feedback and brainstorm ideas on how to use a multilayered approach to educate students and report cases of harassment. Solutions include distributing fliers, online forms, admin-led forums and greater communication with FCPS.

“We have contacted the Office of Safety and Wellness, and they know that the students are interested in modifying that presentation that’s given earlier in the year, so we’ll try to create a conduit to modify the presentation so it addresses what the students feel is important, knowing that it has to be eventually approved by the Office of Civil Rights,” Glazer said. “We have also contacted the police on trying to provide a presentation available to students about online behavior, and so we’re working with the police department, as well as the Office of Safety and Wellness, as well as the students who want to provide their own testimonials about how we can create a forum where students can talk more about issues that happen online that others may not be aware of.”

The end goal of the administration is to encourage harassment victims to come forward.

“We want students to speak up because we care about students,” Glazer said. “We care about students’ well-being. If a student feels bullied at home, we want their parents to know about it, we want to know about, because ultimately we want the students to feel well. If they don’t feel well, it’s impacting their ability to learn. We care about student safety, regardless if it happens in school or outside of school.”

“We want students to speak up because we care about students,” Glazer said. “We care about students’ well-being. If a student feels bullied at home, we want their parents to know about it, we want to know about, because ultimately we want the students to feel well. If they don’t feel well, it’s impacting their ability to learn. We care about student safety, regardless if it happens in school or outside of school.”

The administration plans to continue educating students on how to report harassment in alternate ways, providing support to students who are concerned about safety, providing feedback to FCPS about how to improve sexual harassment education, and educating parents how to respond to harassment concerns that occur outside the school day. Another aspect of the administration’s response involves addressing the concerns that students have raised during town hall meetings and online. Concerns typically raised address reporting, education and awareness, with victims often criticizing the ineffectiveness of the SR&R video on sexual harassment and assault.

According to Sills, this harassment education is only supposed to serve as a baseline for discussion rather than a solution to the problem itself.

“We’re not naive enough to think that if we do a class that everybody’s going to fully understand the full gamut of being harassed,” Sills said. “Our main goal at a minimum is to give everybody in school the same common language so they can say, ‘I feel uncomfortable about something’ and start that conversation.” Nevertheless, Sills has worked with Special Services to conduct focus groups with students and added surveys about safety and harassment to develop effective age-appropriate training to be instituted across the district.

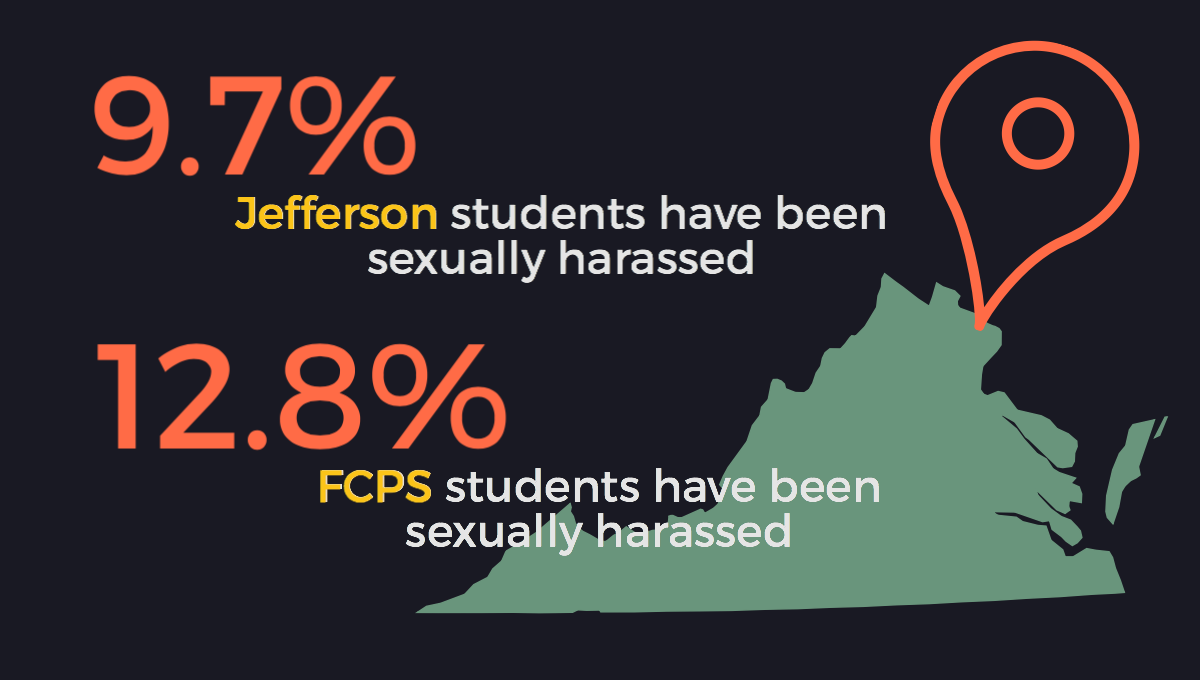

In addition, the Fairfax County Public Schools (FCPS) system revamped its family life curriculum for the 2016-2017 school year by incorporating video lessons as well as extended educational measures concerning consent and assault. With these modifications, FCPS sought to increase early and effective sex education amidst growing national concerns over sexual harassment and assault. On a schoolwide level, Becca believes locally instituted campaigns can also assist with educating the student body.

“At a local level at our school, with individual student-led clubs, we don’t have to worry about getting stuff approved by the greater administration that’s up there,” Becca said. “I think releasing people’s stories like mine, through tjTODAY or through creating personal videos, or just sharing your story, I think would really help, because then people could connect on a more intimate level and understand that they’re not alone.” Changes to FCPS-wide curriculum may be more difficult to implement, Becca said, because “it’s hard to get past the layers of bureaucracy…to get their powerpoint or presentation approved by a Civil Rights Administrator,” a layer of jurisdiction that lies outside of FCPS.

At a local level, counselors and administrators continue offer their support for those who are concerned about issues across the community, aiming for a more open relationship with the student body.

Counselor Sean Burke, who strives to remain “supportive to the students, even the ones that are accused,” similarly urges students to come forward so the support staff can assist anyone in their journey.

If you or someone you know has been the victim of harassment or abuse, report it to the Jefferson administration through this confidential link, talk to a counselor in Student Services, which is located near the Franklin Commons, visit the TJ police officer Officer Richards in the main office, contact Student Safety & Wellness representatives at FCPS, or visit Know Your Title IX to know more about your Title IX rights.

April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month. To find out more, visit NSVRC.org.

Molly • Apr 30, 2017 at 12:39 am

Hello,

I am a senior in high school from California, and I wanted to commend you on the excellent writing and research that went into this piece. I think the issue of sexual harassment and assault in competitive schools, such as TJ and my own, is unfortunately prevalent and needs to be talked about. I’m so sorry for the awful things that the victims have had to go through. I wish your administration would take swift and serious action, and even though that process seems to be failing, you have my support.