Can college admission be bought?

College admissions scandal reveals an imperfect ‘merit-based’ system

A visual representation of the influence of wealth in higher education

March 20, 2019

25 million dollars. That’s how much Lori Loughlin, Felicity Huffman and other wealthy parents decided to spend to ensure their kids got into college.

Background

The largest college admissions scandal ever prosecuted rocked the country on March 12, when the Justice Department revealed charges against 50 people in a scheme created by William Singer. Parents allegedly paid Singer anywhere from thousands to millions of dollars in order to doctor SAT results or obtain credentials for fake athletic recruitments, all in the hopes of sending their children to top-tier universities.

This use of a ‘side door’ to gain entrance into elite schools has sparked a national discussion about the role of wealth and privilege in the college admissions process.

Given the challenging, often hyper-competitive environment here at Jefferson, especially surrounding college applications, it is all the more appalling to hear how some have exploited the system to gain an advantage. More than just a criminal violation of integrity, falsifying application information is not a victimless crime. Bribing proctors for more time on standardized tests undermines the legitimate accommodations granted to students with disabilities. Receiving a sports scholarship based on fake photos and a favorable recommendation from an athletic coach disrespects the years of training earnest athletes undergo to excel at their sport.

Rigging the process cruelly denies ‘front door’ applicants the fair chance they deserve, one that can never be given back to them retroactively.

Singer, and the parents and coaches implicated alongside him, violated the law, and undoubtedly deserve to be brought to justice in court. But their actions have brought to light larger issues within our higher education system that must be addressed.

The ‘Backdoor’

While the illegal activities highlighted in this case have thrust the reality of a merit-based application system into the spotlight, money has always played a defining role in the college process. Families with more financial resources are better equipped to give their kids the best education, test preparation, college advising, and other such college-preparing resources that can mean the difference between an acceptance and a rejection.

But there is an even more overt, though still technically legal, means of buying a college seat. Such a ‘backdoor’ method, which typically involves donating a large sum of money to a school in order to improve admission chances, does not guarantee a college acceptance, but it certainly elevates one’s odds beyond those of traditional applicants. By violating an ethical—or at least conscientious—boundary rather than a legal one, and by providing schools with a valuable source of funds, this practice has stood largely unscathed.

This is the perhaps most baffling aspect of this scandal. Despite having more conventionally acceptable ways to trade privilege for post-secondary success, so many wealthy families still chose to break the law.

We need to implement changes in the college admission systems to prevent another scandal like this, but we also need to cut off some of the legal loopholes we have in college admissions today. While this will be a more complicated process, we believe it’s possible and necessary.

Next Steps

Separation of Book and Bank

First and foremost, we must place limits on the role of money in the admissions process. There is little debate that Singer’s side door should be shut, as bribery, false representation, and outright lies have no place in our education system. But the backdoor needs to be closed, too.

A 2007 study of donation patterns to an anonymous university found that alumni whose children went on to apply there gave significantly more money during their kids’ teenage years—leading up to college application time—than alumni without children or with children who didn’t apply. This data indicates that the decision to donate is at least partly influenced by the desire to attend a school, which suggests that families believe donations can impact college acceptance.

Such a perception is only confirmed by universities’ actions, such as Princeton President Shirley M. Tilghman’s statement that alumni donations are “extremely important to the financial well-being of [the] university.”

Higher education is one of the few ways that individuals from lower income communities can surpass their socioeconomic status. To give wealthier students spots simply as a result of their money, or even imply this occurs in order to increase donations, does a disservice to society. If we are against money being used to fake SAT scores, then we should also be against donating a similar amount to a school for an almost guaranteed acceptance.

Preventing schools’ admissions offices from accessing donation information can put an end to this unofficial quid pro quo, or advantage-seeking favor, system. Doing so may cost schools some donation money, but colleges are institutions of learning, and should hold themselves to an ethical standard rather than a capitalistic one.

Oversight

This case has proven that along with minimizing the influence of money, sharing responsibilities between multiple individuals is crucial for a fair system. Singer’s scheme would not have been as effective if the bribed test administrators and coaches couldn’t act alone to game the system. When it comes to proctoring tests, recruiting athletes and ensuring the validity of records, nothing should be the responsibility of one person.

Cultural Shift

But these tangible changes will only aid so far in making differences in the current college admission system. Often times, the factors that build the collegiate admissions process are internal, requiring a tedious process to change the culture of the college admissions.

At the heart of Singer’s scheme is the influence of the parents. Some of the students who were unethically admitted allegedly had no clue about their parents’ actions, instead believing they had earned their spot at an elite institution fairly. In other cases, such as with Lori Loughlin and daughter Olivia Jade Giannulli, the parent wanted the college spot for their child more than the applicant did.

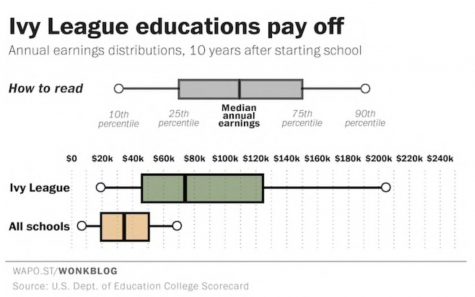

Graph comparing education and salary of university graduates.

This calls into question the pressure placed on student to attend prestigious schools. A graph in the Washington Post, which summarizes data from the U.S. Department of Education, shows that Ivy League graduates earn more than double the salary of graduates from other schools ten years after college.

But at a closer glance, the ability to attend an Ivy League school or other competitive colleges does not accurately rank students’ intellectual abilities. In fact, a student’s qualifications may be a better indicator of their future salary than their college.

When adolescents begin looking for a future college, they often look toward specific programs for intended majors that can best educate and serve them in a career of their choosing. While the names of prestigious colleges can serve as stepping stones to “success” for some, many individuals society considers successful did not attend the top ranked universities or even attend college at all. Ellen DeGeneres, Steve Jobs, and John D Rockefeller all did not graduate from a university. The emphasis on success truly boils down to how we have come to define success and its reliance on titles and names.

Disseminating a new definition of success could be the beginning of a cultural shift from aiming for top schools to aiming for top students. No matter where students end up in their college decisions, the values they maintain and the strengths they carry should hold as the main contentions in determining the success of students for the next four years and beyond.

Many questions remain to be answered as this case progresses, including what consequences children who weren’t aware of their parents’ actions should face. But one thing is clear: money can strongly influence college admission decisions, both legally and illegally, giving wealthy students an unfair advantage. If we want everyone to have an equal opportunity to education, that needs to change.