(Un)Equal opportunity: Breaking down demographics at Jefferson

The release of Jefferson’s admissions statistics highlights inequality in the process

June 20, 2020

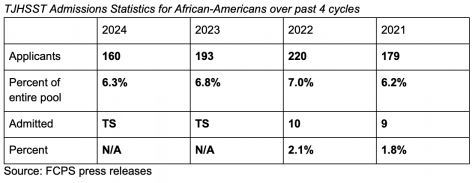

‘TS’. Again. Another year, another disappointing number. Or lack thereof.

Established in 1985, Jefferson has an extensive history as a magnet school. Not only does it promote excellence in STEM education, but a core aspect of Jefferson’s mission statement is understanding the “languages, systems and diverse cultures of people throughout the world.” Nevertheless, the recent release of admissions statistics for the Class of 2024 once again draws attention to the lack of diversity at Jefferson.

Instead of releasing a number for how many Black students were admitted this past admissions cycle, the table shows “TS,” which stands for “too small for reporting.” This abbreviation is used to represent a demographic of fewer than ten, to prevent the identification of these students. After the initial claim that zero Black students were admitted, administration officials have clarified that the number of Black students admitted was in fact greater than zero.

With the increased focus on the Black Lives Matter movement and the protests erupting across the nation, the letters “TS” shed light on one example of racial inequality in our own community.

The discrepancies

The lack of Black students in the Class of 2024 is not an aberration: fewer than 11 Black students have been accepted in each of the past four admission cycles. Furthermore, according to the most recent statistics, less than 6.3% of Black students who applied were admitted.

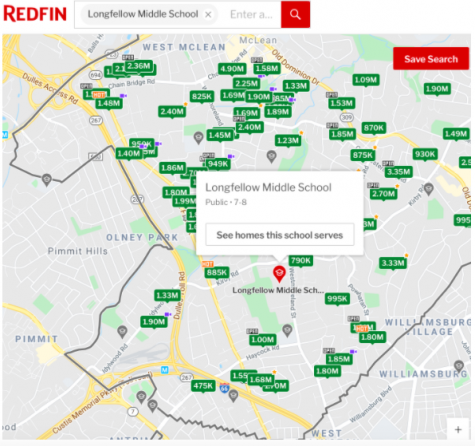

One explanation for the lack of students from underrepresented groups is the income gap between different races. According to a 2017 US Census Bureau Survey, the median household income for Black families in Virginia was $49,562. For Asian and white families in Virginia, that number is closer to $100,000. This income gap accounts for a difference in resources available to students, including access to adequate test prep, early enrichment programs, and “feeder” middle schools. Communities which are zoned to the “feeder” schools tend to have more expensive housing, making it more difficult for low-income families to access them.

Test prep centers are one of the biggest ways students gain an advantage in the admissions process, with both external prep centers, as well as a prep class offered by Fairfax County Public Schools (FCPS) through Adult and Community Education (ACE). FCPS’s program costs a total of $445, whereas an external test prep program offered by a private company costs approximately $2,100 per year. The use of test prep programs benefits students who come from wealthier families, failing to take into account students who are unable to afford the extravagant cost of preparing for the admissions test.

“I believe there’s an opportunity gap. There are many families who may not have the ability or the means to start preparing their child very early on with summer STEM camps, test prep, and other kinds of things,” Jefferson principal Dr. Ann Bonitatibus said. “I don’t believe that our current admissions tests and processes provide opportunity for all students who are qualified to be able to really make it through the admissions process.”

Approximately 28% of students in FCPS qualify for free or reduced priced meals, and 73% of those students identify as Black or Hispanic. However, as of 2019, the percentage of students at Jefferson receiving free/reduced priced meals is 1.98%. This gap contributes to the lack of diversity at Jefferson, as it demonstrates that Jefferson students are a wealthier group of students in comparison to the rest of the FCPS.

The Advanced Academic Placement (AAP) program, which is often deemed an early indicator of academic success, is another area where inequality exists.

“I believe there are not multiple pathways for a variety of students to access from very early on. It seems like the one and only pathway is the Advanced Academic Program, and it seems like most students who come to TJ have been through that track,” Bonitatibus said.

Though 36% of FCPS’s demographic comprises of Black and Hispanic students, they only make up 18% of students in Level IV AAP classes. By comparison, the percentage of Asian students in FCPS is approximately 19.6%, but they make up 32% of Level IV AAP classes. Interestingly, the percentage of white students in Level IV AAP classes (38%) almost exactly mirrors the percentage of white students in FCPS (42%).

Students taking part in the Level IV AAP programs continue to do so in middle schools that are AAP centers. These middle schools are equipped with more curricular resources and extracurricular opportunities. They often end up sending higher numbers of students to Jefferson, and have been unofficially coined as “feeder” schools. Based on data for the Class of 2021 admissions, of the eight middle schools sending more than 10 kids to Jefferson, seven of them are full-time Level IV AAP centers.

Rising senior Didi Elsyad is one of few Black students in the Class of 2021. She believes that the cards are stacked against underrepresented groups at Jefferson.

“Minorities are more likely to be low income, so they can’t afford all the prep classes many people here can, and they are less represented in the AAP programs. When you combine these two factors together, you realize that many of those kids never really had a chance,” Elsyad said.

But the effort to increase the population of underrepresented groups at Jefferson is one that has remained unfinished since the early 1990s.

Past attempts

In 1992, the district introduced race-based quotas to admit more Black and Hispanic students. Legal rulings and challenges against quota systems at the local and federal levels prompted the district to eliminate the quotas in the early 2000s.

Following this, the admissions office shifted to a system which ignored race, and instead focused on expanding admission of students from underrepresented middle schools. The district discontinued this practice after it failed to significantly increase the number of Black and Hispanic students.

Admissions officials subsequently eliminated a cap on the number of students eligible to become semifinalists, established a wait list, and emphasized evidence of passion for STEM as opposed to achievement in STEM in their application. Currently the admissions process does not consider race, gender, and socioeconomic status as factors for admission. In 2013, the application review process shifted to a holistic review, which allows a student to be evaluated within the context of their middle school.

“When an admissions evaluator is reviewing an application and they’re coming to a final conclusion, they can look at the student’s middle school to see the math classes offered at their school, and the highest level of math the school offers. This adds a lens for us when evaluating the student’s application,” Director of TJHSST Admissions Jeremy Shughart said.

Both Jefferson and the TJHSST admissions office utilize outreach initiatives. Programs such as Visions and Quest provided mentoring and enrichment to low-income and students from underrepresented groups, but were determined to be ineffective and phased out before 2010. Since then, the Jefferson community has started other initiatives such as Young Scholars and Learning through Inquiry, Fellowship, and Tutoring (LIFT).

Class of 2020 alumna Amita Goyal was involved with Women Interested in Science and Engineering (WISE), and served as the president in the 2019-2020 school year. Students involved in WISE volunteer at Weyanoke Elementary School, mentoring students with enriching STEM activities. Goyal believes in the value of such initiatives, but wishes such programs did more to develop a lasting connection with students.

“Most of the children we interact with in fourth and fifth grade say, ‘I’m gonna come to TJ,’ or ‘I’m gonna be there one day,’ but then something changes and they don’t apply in eighth grade or they don’t get in,” Goyal said. “We need to make sure that these programs don’t end when the school year ends, and ensure that the relationships with the students last through the TJ admissions process.”

Future steps and why diversity matters

As frustration grows around the lack of Black and Hispanic representation at Jefferson, students and faculty have proposed several ideas to help address the problem. Elsyad, who had some uncomfortable experiences when she first entered Jefferson, advocates against affirmative action through a quota system.

“There isn’t any affirmative action now, but when I got in, some accused me of only getting in because of a quota. I can’t imagine that affirmative action would genuinely help those students,” Elsyad said. “The lack of diversity is not the fault of TJ admissions. It’s the fault of systemic racism that can be traced back to very early on in a kids life, and it can be traced back in our history to the days of slavery.”

Another argument against reverting to a race-based quota system is that it doesn’t address the actual problems our community faces.

“It’s important to acknowledge the reality of the political climate when attempting to enact change,” former SGA president and Class of 2019 alumnus Neil Kothari said. “I think efforts should be focused on more politically feasible goals that work to address the root cause of the issue instead of mere ‘band-aid’ solutions that would occur too late in the process.”

Chemistry teacher Robin Taylor, the only Black teacher in the Science and Technology department, believes that additional steps need to be taken to train teachers on writing recommendation letters, especially since some middle school teachers are unfamiliar with Jefferson’s mission.

“Middle school teachers may benefit from a little more direction about what is important in identifying students that would be successful at TJ and writing positive recommendations for these students,” Taylor said.

Making Jefferson a place where students from underrepresented backgrounds envision themselves might mean dismantling a mascot that has symbolized racism and class-based discrimination. In a recent email to the Jefferson students and families that addressed racism and equity, Bonitatibus asked the community to consider the meaning of the Colonial mascot.

“When I first came to TJ, I had a lot of questions about colonials as a mascot and how that even survived for so long,” Bonitatibus said. “I feel that now is really a time to begin the conversation, because sometimes when we want to change things that are institutionalized for decades, there’s a readiness factor. We can create another mascot or symbol that represents us and that we can be proud of, and really that’s where I’m interested in going.”

Ultimately, the added benefit of a Jefferson that represents the racial and socioeconomic diversity of Fairfax County cannot be understated. The value of being exposed to a variety of backgrounds, cultures, races, and religions is equally as important as a premium education.

“The reason why diversity, and particularly equity is really important is that we want to make sure that students have experiences that prepare them for the world. We build appreciation and acceptance of each other when we’re able to be in a diverse environment,” Bonitatibus said.

Though being from an underrepresented group at Jefferson is difficult, Elsyad acknowledges that the quality of education a student receives is worth it.

“Being a minority here has really gotten to my head at times, and I just feel like maybe I’d feel less like an outcast sometimes if there were more Black and Hispanic students,” Elsyad said. “Is a top notch education worth being an outcast? Now I can say yes, but it was a very long road to get there.”