“The Birth of a Nation”: D.W. Griffith’s ultimate argument for hate

“Like writing history with lightning.” – Woodrow Wilson, president, racist

July 29, 2020

Author’s note: I was originally planning on writing a fun article about why you should watch silent movies, which led me to watch “The Birth of a Nation” so I could write a throwaway sentence saying you shouldn’t watch it. I was so deeply disgusted that I couldn’t in good faith just write it off.

I hate being hyperbolic, but I think that “The Birth of a Nation” (1915) might just be the worst movie ever made. This movie is despicable. It’s so insulting on every level that it’s difficult to keep up the veneer of professionalism that I try oh so hard to maintain. Even calling it a film seems blasphemous – this isn’t even a film, it’s propaganda. It’s propaganda for an ideology so heinous that it makes me even angrier that some people agreed with it when it was made, and then caused a resurgence in the Ku Klux Klan! Movies don’t do that! Propaganda does! And then, to add on to that, this piece of flagrant racist propaganda is lauded by film scholars across the world as one of the early masterworks of cinema! With this review, I intend to use what little power I have not only to tear down “The Birth of a Nation”, but to inform you about its horrible legacy.

I’d like to start my analysis of the movie by refuting the worryingly widespread belief that “The Birth of a Nation” is a revolutionary piece of filmmaking. It isn’t. In fact, just about every aspect that D.W. Griffith would like you to believe that he pioneered in “The Birth of a Nation” had been done before him. People claim that Griffith invented the dramatic close-up, but it was used better in “The Great Train Robbery” (1903). That movie also pioneered intercutting, “Dante’s Inferno” (1911) introduced tinted frames, and every other “innovation” had been done by someone else. The only revolutionary thing about “The Birth of a Nation” is its budget, which allowed Griffith to throw hundreds of extras at the screen and advertise that he did everything first.

Speaking of which, Griffith wasn’t a great filmmaker. This movie is one of the most lazily shot films I’ve ever seen, even noting the low standards of the time. Apart from the three close-ups (four if you count the close-up of cats that’s supposed to make you like the southern slave owner), there isn’t an interesting shot in the movie. This problem is compounded by the lack of consistent title cards, which are essential to get right when you’re making a silent film that’s blocked like theater. Speaking of the title cards, like everything else, Griffith loved to slap his name on it, and included it on the borders three separate times.

But in a discussion of “The Birth of a Nation”, the filmmaking is hardly the most important talking point. This movie is structured in two parts: the “tragedy” of the South losing the Civil War, and a revisionist version of the Restoration which focuses on the “horror” of equal rights. The first half of the movie isn’t good by any standards, but it’s almost excusable. However, the Restoration period segment is abhorrently racist at every opportunity. The second half follows Ben Cameron, the protagonist and founder of the Ku Klux Klan, and his fight against Austin Stoneman and his half-black protege Silas Lynch, who want to secure equal rights for African Americans.

Austin’s push for equal rights results in a hellish dystopia of Griffith’s imagination where equality among the races immediately leads to the subjugation of rich white people and mass pandemonium. Griffith portrays the black population as this overwhelming mass that’s both too powerful, but also too stupid to understand what’s best for them. Not to mention that every single black character, apart from a few extras, isn’t even black, but rather a white actor in blackface.

There’s also a strange fascination with the black male’s sexuality. It’s demonstrated most in a telling scene after equal rights have been established where an all-black Senate congregates over the establishment of inter-racial marriage. The congressmen lear at white onlookers with devilish smiles, because Griffith has to drill into your head that black men are to be feared. At every opportunity Griffith can get, there’s a scene where a black man tries to assault the purity of a white woman, which ultimately leads to the protagonist starting the Klan. This is followed by a lynching which is sickening to watch, even though it’s trying its best to seem heroic.

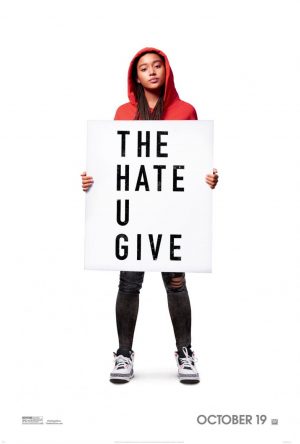

“The Birth of a Nation” is utterly deplorable. It’s impossible to truly understand the scope of both its depravity and general incompetence without actually seeing it, but I obviously couldn’t ever recommend that. What I think is the biggest problem with “The Birth of a Nation” is that people keep watching it. People keep praising the chases and final action scene, without realizing that they keep gushing about a three-hour hate crime. This movie is only important because it serves as a perfect showcase of how people actually thought back then, and in some cases, still think today. Don’t see it, I already regret doing so myself.

Yeaton Clifton • Jul 29, 2024 at 5:47 pm

This should be considered the most violent movie in history. When discussing violence it is often pointed out that there is no direct correlation between third rate horror films and actual violence. This movie certainly inspired violence, and can be directly linked to more violence than any other movie in history. I would like to deduce how the director responded to violence against blacks, Jews and Roman Catholics inspired by his film. His follow up described “intolerance” by Roman Catholics (French), Jews (Ancient) and Women (Reformers). The fourth group of intolerants were a group of Babylonians who have no particular relavence to the present. But, the question is whether if you stir anger against groups you consider intolerant, how do you avoid the kind of black and white morality that provokes violent response. Do the Right Thing certainly urges whites to seek more tolerant attitudes rather than suggesting the intolerant should be routed out and destroyed. In Malcolm X, the hero was more tolerant of other groups at the end than he started. Yet the anti-woke cancel culture speaks as if Spike had done something horrid. It is not clear whether Griffith’s use of stereo types in Intolerance was ever discussed in his lifetime, or why he thought it was not harmful, just like there no obvious references to his response to violent nature of his films.