Stopping the spread from home

As part of a series to inform current Jefferson students about future career paths, tjTODAY talked to Gretchen Buckler, an epidemiologist and Jefferson alumna.

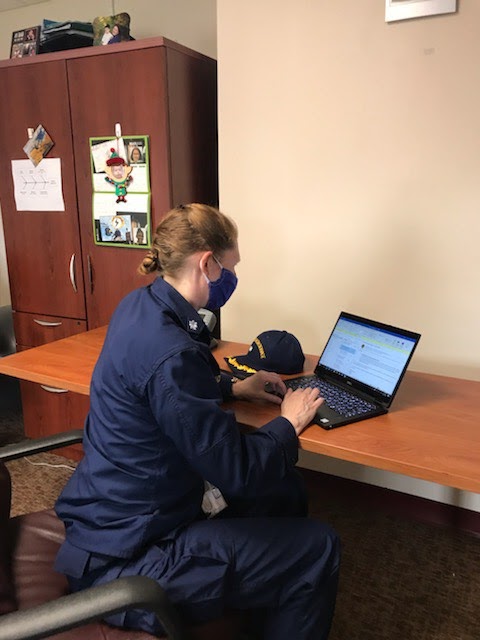

Jefferson alumna Gretchen Buckler sets up contact tracing for the Delaware Department of Health in May 2020.

February 2, 2021

Note: This article is part of a series where we ask Jefferson alumni to describe a day in the life of their careers, to help Jefferson students explore and evaluate different career paths and options.

Uncontrolled diseases. Endless coughing. Many more deaths. This would be the reality for millions of children under the custody of Customs and Border Protection if people like Jefferson alumna Gretchen Buckler were not there to assist.

Before the pandemic, Buckler (Class of 1991) would spend most days at a public health service office in downtown Washington, D.C., coordinating response and isolation of infectious diseases in unaccompanied minors crossing into the U.S. via the Mexican border.

“I’m on what’s called the public health service, in the communicable diseases response team, so in regular times, we mainly check on varicella (chicken pox). [When kids are found to have chickenpox], we have to figure out which kids they were in contact with, because those kids have to be quarantined, in separate rooms, kind of like we do for COVID,” Buckler said. “We also do a lot of testing for syphilis, HIV, and any other kind of infectious disease that could be spread amongst the populations.”

Most of what Buckler does involves working with different shelters and unaccompanied minor programs via email to ensure that outbreaks are caught and contained quickly, and appropriate precautions are being met.

“We’re overseeing and making sure that [the shelters and programs] are doing all the things they’re supposed to do with the CDC’s changing guidelines,” Buckler said. “[Another] one of the things we try and do is in our computer system, you can link up which kid exposed which other kid, there’s a complicated way to do it, so once we finally get them linking everything correctly, then we can actually use the data and statistics to see if we can figure out things.”

Now, things are largely the same, except Buckler works from home, and coordinates mainly COVID-19 response instead of chicken pox and other diseases.

“With COVID, we basically do the same thing except for we now have it set up so we quarantine them for 14 days, as if they’ve been exposed, because we never know if they’ve been exposed or not,” Buckler said. “And then we test them right when they show up for COVID with a PCR test.”

To Buckler, epidemiology has many highlights, like forging connections with people at unaccompanied minor programs. She also cites the satisfaction of stopping the spread and being able to see her team’s impact in the statistics.

“It’s always good when I catch a kid that’s got COVID before I let him go on a plane, that makes me like I haven’t exposed anybody else,” Buckler said. “We were [also] finally getting to the point where we’re able to do a little bit of data analysis, which is going to be once we finally get some downtime. The data analysis part is going to be kind of satisfying– to see how the disease transfers around our programs and whether the staff are giving it to the kids or the kids are giving it to the staff.”

Buckler notes that not all epidemiologists work in offices monitoring infectious diseases. Epidemiology often includes direct fieldwork and patient interaction too, which Buckler’s previous job as the deputy state epidemiologist of Iowa involved.

“We would do foodborne [illness] outbreaks, so we’d go out into the community and we’d meet with the people who are sick,” Buckler said. “[So] if you have a foodborne outbreak at a party, you make a list of all the foods people ate, and then you ask every person who ate a food and everybody who got sick. Then, you can make this two by two table and figure out statistically which food it was most likely that made the person sick and then you can track back and see what went wrong with the cooking of the food.”

Epidemiologists are notably involved in current efforts with the COVID-19 pandemic as well, like contact tracing. However, Buckler highlights that there are other areas of scientific focus in the field.

“It’s not all infectious diseases either, there’s a lot of epidemiology done in chronic diseases. The CDC has got tons of data on people who have heart disease or high blood pressure [or] diabetes,” Buckler said. “So you can look at different aspects of their background and their demographics, their age, their race, their gender, [if] they smoke, [if] they drink, what kind of diet they have, and you can look for correlations between all of those things.”

Buckler explains that epidemiology is perfect for those who are interested in medicine and data science, but do not necessarily want to see patients.

“If you’re interested in medicine, if you’re interested in health aspects, and you’re decent with math and data kinds of things, but you don’t really want to do lab based research, and you don’t want to see patients, [epidemiology is a great option]. [For example], I get nervous when I see patients. That’s one of the reasons I’m sort of in the less patient focused area of medicine.” Buckler said. “[Epidemiology is] ‘desk medicine’. I sit at my desk, [but] I use my medical school skills to do medical kinds of things. It’s a type of population medicine, so you get to help a lot of people.”

Buckler also mentions that there are new and interesting ideas and methods coming along in epidemiology.

“There’s all kinds of cool things you can do with data now, you can even do analytics with things like Facebook, using how often people mentioned that they’ve got cold symptoms and see if that like tracks back to the rate of flu in a community and things like that,” Buckler said.

Finally, Buckler adds that many classes at Jefferson were an inspiration in her journey to epidemiology.

“When I was at TJ, I took anatomy and physiology and I took health technology, those two classes helped get me more interested in the medical side of things. And I [also took] a logic math class, which has got a lot of the probabilities,” Buckler said. “Probabilities are a big aspect of epidemiology, [since you’re] figuring out the likelihood ratios of, for example, ‘if you’ve got this symptom and that disease, what’s the likelihood you’re gonna get whatever disease from that?’”