Diversity in history

February 13, 2022

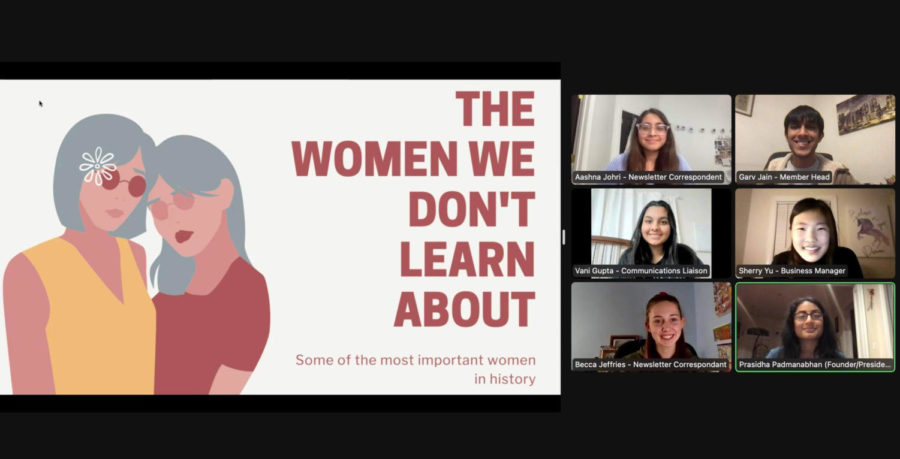

Image courtesy of Prasidha Padmanabhan

Jefferson students are spearheading a change in FCPS history curriculum to represent more women and those of an underrepresented minority. Members of WEAR give a presentation on important female figures in history whose stories aren’t taught to many students.

Look at the current decisions and legislation that has been passed within the past few weeks in Virginia and the United States. From changes that may affect you, a family member, a friend, or someone on the other side of the country, each law and choice being made by a person in the government has a huge impact on every single person living in this country and around the world.

In order to understand the choices in the world that are being made, it is imperative to learn and have a well-rounded understanding of history.

“Learning about history is important because it gives us perspective for our current time,” senior Micaela Wells said. “Knowing what happened in the past helps us to not repeat that, as a lot of people say, but also it helps to understand the trends that we face now and what we see happening in the world now.”

By studying history, a student better understands why the world works the way it does. History is completely interconnected, with actions happening in one place changing the way society functions in a country on the opposite side of the world.

“Once you start studying history, you realize—and I tell this to my students all the time—this idea of pulling threads,” Parie Kadir, a World History and Advance Placement (AP) U.S. Government teacher at Jefferson, said. “There’s no one thing in history that’s just a single event, it’s once-off, and it doesn’t connect to anything. It’s completely interconnected. Everything about history is about these threads that you pull on.”

However, the standard history curriculum in Fairfax County Public Schools (FCPS) isn’t completely representative of what happened in the past. A textbook that closely follows the AP U.S. History curriculum, for example, only covers women in World War II for one paragraph before moving on, as Wells wrote in a Washington Post opinion piece.

“To a large extent, women and people of color, their history has been lost, or it’s not being told, even if it hasn’t been lost. That means we’re really only getting half the story, not even half the story,” Wells said. “If we don’t learn about [their history], then we’ll never be able to understand why what’s happening in our world now is happening and why it’s affecting people this way.”

Another direct effect of not teaching a representative curriculum in history classes is showing students that they don’t matter as much as another does.

“When you discount a group or someone from history, what ends up happening is you erase them from history,” Kadir said. “And oftentimes when you think about it, if you don’t bother telling someone’s story, then what does it say about them? What does it say about their experiences, what does it say about their history, what does it say about their contributions?”

One of the only things that exists in schools to try to reverse this lack of representation issue is highlighting the history of certain groups of people in certain days, weeks, or months.

“We’re in the middle of black history month and next month is women’s history month. And this idea that you can take the entire history of a group, put it in one month, and then just write off that group for the rest of the year is absolutely insane,” Kadir said. “I do think that they are so important and so vital to raise this awareness. What I hesitate in having it is that people think if you do this, then you don’t have to do anything else. And that’s where my issue comes in.”

The history of many groups of typically underrepresented people have designated months to learning them, also including Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month in May and National Hispanic Heritage Month from Sept. 15 to Oct. 15. And while many FCPS history teachers attempt to focus slightly more on teaching the history of these groups during their designated month, it can be difficult because they are employed by FCPS and still have to follow the set guidelines.

“As employees of the county, [teachers] are people who are teaching the county’s curriculum. I don’t know how much movement you get from advocacy there,” Kadir said. “But I think from parents and students, absolutely. That is where you are going to see the most shift and movement in curriculum.”

If you are looking for ways to diversify your history knowledge, there are many things that you could do.

“We have libraries—we can go to the library and we can check out books. And we have the internet—we can go online and learn about all of these amazing women throughout history—but I think what really needs to happen is it needs to not be optional,” Wells said. “It shouldn’t be an elective if I’m interested in it. It should be something that’s mandatory to learn about because we’re excluding over half of our population from what their history is.”

That change to history curriculums in FCPS schools and across the board entirely is necessary to accurately teach history to students of all grade levels, but there are things to keep in mind before trying to invoke change.

“I think the first step is understanding what the current curriculum is,” Kadir said. “A lot of people immediately start talking about change without knowing where we are. So I think the first step is, ‘Well what is the current curriculum? What are we learning?’ and then taking a hard look and saying, ‘Well, what do I want to see that’s different’ and mapping that out. Then saying, ‘These are the changes I would like to see or this is what I would like to see and this is what I would like it to look like.’”

After curating specific things you wish to include in history curriculums at FCPS, look to providing resources and ideas for FCPS officials to look through and implement. Also make sure to do research and study different points of view for any event in history.

“It’s not just from one group or another group, but look at their perspective and look at what was happening to these individuals at certain points in history,” Kadir said. “And then [get] engaged with the different levels from the school to the county to the school boards and talking with them, ‘These are things we are interested in. We understand how it works, we understand how these changes can be implemented, and here’s our suggestions.’”

Another possibility includes participating in the Historical Marker Project, a joint project by the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors and FCPS. The Historical Marker Project is currently focusing on African American history but has plans to expand to other underrepresented stories within the next few years. Any student from grade four through twelve can submit untold stories of local historical figures and submissions will be accepted from Feb. 1 to Mar. 31. Applications are accepted here.

Women for Education, Advocacy, and Rights (WEAR) is an organization created by junior Pradisha Padmanabhan that focuses on including more women in the history curriculums taught at FCPS.

“[If interested], definitely go to our website and there’s a registration and members button,” Padmanabhan said. “You can also email us at [email protected]. We love [getting] in touch with people and [getting] them involved if they want to.”

Ultimately, understanding the full history behind how we came to be the people and nations we are today is necessary to making informed decisions and fully understanding what is going on in the world.

“I turn 18 this year and I get to vote in nine months,” Wells said. “I get to make decisions now and I need to learn and I need to know what implications my decisions are going to have. It’s going to be our world, we’re going to be the people in power, and we need to understand how our decisions are going to affect people. Learning [everyone’s] history will give us a much broader perspective and a much better foundation to make those decisions for.”