The Inside of Integrity

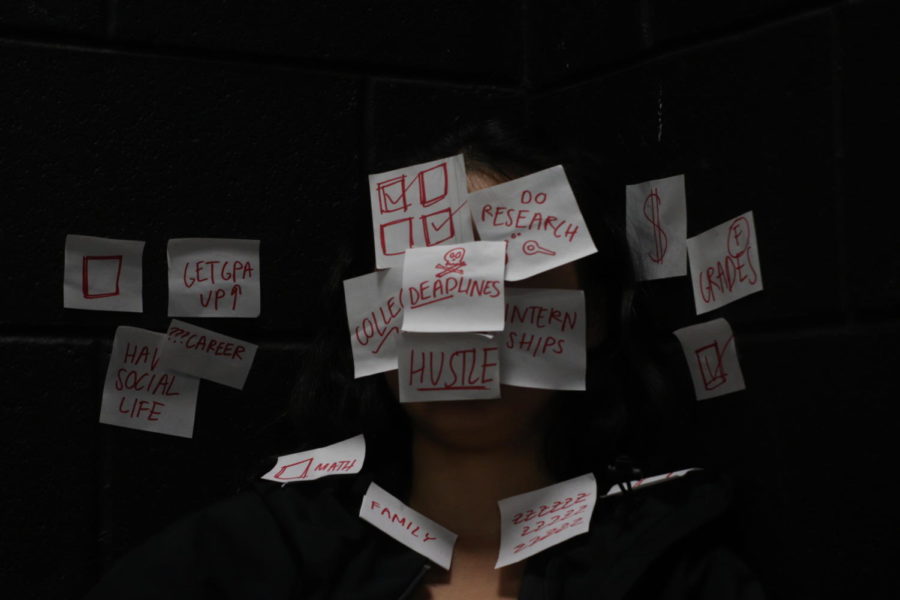

Overwhelming workloads and expectations, induced by mindset or the environment, are factors that cause students to cheat on exams and assignments during high school. “They pile this much work onto you, and then expect you to have all the time in the world to complete it,” sophomore Fertuna Mequennent said. “Cheating is more than just a kid who’s lazy or doesn’t want to study.”

May 2, 2023

“You may begin.”

The timer projected on the whiteboard begins to tick. An hour and a half. 1:29:59. 1:29:58. 1:29:57. After flipping open the pages in front of you, you realize you don’t know how to do question one.

1:29:30.

You should’ve studied more. But with basketball practice and physics homework and chemistry labs and math packets, how could you have found the time?

1:29:20.

You think of your grades, of college applications, of your future.

1:29:10.

You glance at the classmate beside you. Then down to their scantron.

1:28:59.

It’s wrong. You know it’s wrong.

But you bubble in their answer on your paper.

To collect information about why students commit integrity violations, tjTODAY posted an anonymous Google Form on TJ’s Intranet (Ion), and received 167 responses. According to the survey, 56.3% of the responses reported that they have cheated on a graded assignment during their time in high school.

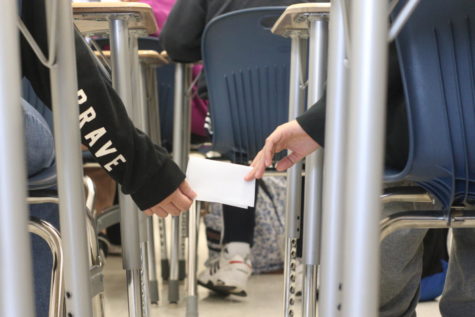

“‘I’ll just copy off your answers for the Geosystems lab,’ or, ‘Really quickly, the teachers are about to check our homework, can you just show me what you did so I can just copy it off?’ It’s in cases like that where I feel like the cheating culture has really become normalized,” Honor Council vice president and senior Patrick Bai said.

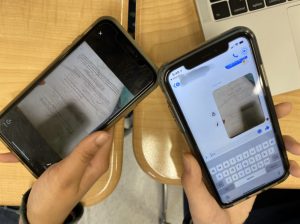

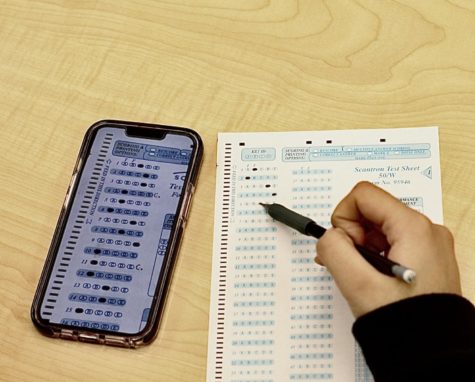

Another 26.9% of respondents to the survey reported that they have cheated on a test or quiz, which can affect all students in the class, not just those who cheated.

“Several years ago, there was an issue with cheating where somebody took pictures of a physics midterm and then every single class lost the curve,” senior Emma Cox said. “There’s definitely a mentality that this whole issue is teachers versus students, but I don’t think that’s true.”

Jefferson students who witness others cheating are unlikely to report it. Only 7.5% of respondents to the tjTODAY survey reported an integrity violation after witnessing someone cheat on a test or quiz.

“Students who cheat probably don’t think they’ll get caught, because I’m sure a lot of it goes uncaught,” counselor Kerry Hamblin said. “They may not report because they are afraid of retaliation. Nobody wants to rat out a friend.”

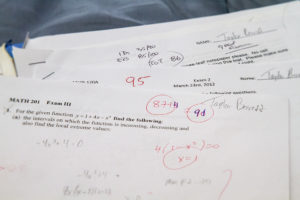

Instead of immediately confronting a student that he suspects is cheating, physics teacher Adam Smith begins to photocopy the student’s tests. Through that process, he noticed that students who begin to cheat tend to continue cheating on future assessments.

“Once you open that door and go through it, it is very hard to walk back out and close it again,” Smith said. “You will often think ‘Hey, I’m just gonna do it this once because I’m really stressed this time, but I won’t need to do this again.’ And it never works like that.”

Choosing to Cheat

After succeeding academically in middle and elementary school, Jefferson’s rigorous courses can be an adjustment for freshmen, who maintained at least a 3.5 GPA in middle school, a requirement to apply to Jefferson.

“People are afraid of failure,” Cox said. “Especially at the beginning of our high school careers, we’re not used to seeing low grades, and I think that might contribute to people feeling like it’s necessary to cheat.”

Pressure to succeed academically contributes to increased levels of anxiety among Jefferson students, evident in the Social Emotional Learning (SEL) screener all FCPS students took in October.

“Students are indicating in the SEL screener and other climate surveys having anxiety more than depression or stress,” principal Ann Bonitatibus said. “I’m wondering if anxiety would be a trigger for academic dishonesty if you’re anxious about how you will do on the assignment or test.”

The academic pressure amounts to more than a grade or test. Either from self, peer, or parental pressure, students face expectations to achieve high grades to gain admission to top-ranked colleges.

“It’s about wearing that sweatshirt once you get accepted, and walking around the halls and having everybody admire you,” math teacher Michael Auerbach said. “They want [it] so bad that they’re willing to do anything to get it.”

When a focus on achievement and college pressure come together, students can feel that they have to cheat to avoid failure.

“From going [to Jefferson], I developed this need to be perfect and excel and not fail and just keep going,” Jefferson alumna Adithi Ramakrishnan, who graduated in 2018, said. “I feel like that also might be affecting the cheating culture in the sense that every student feels like they have to be ‘on’ all the time, and if not, they’re failing.”

Hearing from college graduates about how little college reputation matters in the long run can reduce that pressure on students.

“Maybe we just need to present to you guys the outcomes that you’d be surprised by. The kids that go to James Madison and George Mason end up doing as well as some of the Ivy League kids,” Burke said. “I think sometimes we do a poor job at TJ of showing you what the outcomes are down the road.”

Making Changes

In 2018, Jefferson enrolled in Challenge Success to improve students’ overall wellbeing. The Challenge Success program aims to decrease workload and prioritize mental health in partner schools, among other goals.

“When I first came to TJ, wellness was an issue because of high pressure and a highly competitive environment, so we needed to attend to the physical and mental wellness of our students,” Bonitatibus said. “I made that my transformational mission and we joined the Challenge Success network of schools.”

One of the main goals of Jefferson’s Challenge Success program was to decouple workload and rigor. The program encouraged teachers to reexamine the work they assign.

“Teachers have become more aware of what their workload does to kids, especially with some of the exercises where kids and teachers would switch for a day and the teachers go through the kids’ schedule. That was a Challenge Success idea, which was brilliant,” Burke said.

According to Fairfax County Public Schools (FCPS) guidelines, high school teachers should assign about two hours of homework per week, another limit on how much work a course can have.

“I personally do less assigned reading than I used to,” biology teacher Aubrie Holman said. “We kept the things that were most meaningful, and we have digital tools that we can use post-pandemic.”

Despite the decrease in workload, the amount of time a student puts into a class can depend on the rigor of the course.

“If you still have to learn BC Calculus, you still have to learn BC Calculus, whether the teachers are assigning you ten homework problems a night or 50 homework problems a night,” math teacher Kathleen Juster said.

However, teachers can prioritize certain assignments to reduce workload without changing the difficulty of a course.

“I don’t assign any homework. I think having a few priority items in a class as opposed to a lot of little assignments makes it more likely that the students are going to do their own work,” chemistry teacher Emily Owens said.

To achieve a more manageable workload, the gradebook can weigh effort and assessments equally, rewarding students for hard work.

“I always try, especially with freshmen, to balance a minor quiz grade with another minor grade, ideally something that prepared them for the quiz,” Holman said. “I’m trying to teach them that good preparation is just as important as performance.”

Another method of reducing homework is to increase the class time that students have to complete assignments.

“[Students] have the time to work on this and can ask other people to help. But chances are, because you both have the designated time to do it, you’re actually going to talk about how you did it, as opposed to just copying it,” Owens said.

With the previous approaches, a less-overwhelming workload can decrease cheating. But in the short term, teachers can adjust methods of testing to prevent students from being able to cheat at all.

“This is gonna sound horrible, but teachers need to come up with different assessments. You can’t roll off the same tests period one through seven because everyone shares information,” Burke said. “We have to accept that [students] are social creatures, that you guys want to help each other, and that it’s so hard to tell a friend, ‘I can’t give you help on this.’ It’s nearly impossible. We need to create different ways to assess people’s understanding of the concepts we’re teaching.”

Since Blue Day classes typically take quizzes or tests before Red Day classes, the later periods have the advantage of information being spread within the student body. To combat that difference, teachers can vary the order in which class periods take tests.

“Staggering tests would be helpful, like sometimes having [the first test] be in fifth period and [other times] first period, especially for pop quizzes,” Cox said.

Student Solutions

Teachers aren’t the only ones responsible for reducing workload and stress. Students just finished selecting courses for the 2023-2024 school year, and these choices will influence their workload during the school year.

“In one breath, I come from a meeting about how to reduce stress and anxiety, and then two seconds later, I’m signing kids up for AP Chemistry, AP Physics, BC [Calculus], or AI. The choices that students make directly impact their level of stress, and they think they can handle it and then it comes and they can’t,” Hamblin said. “We don’t want to entertain any more conversations about stress because you are choosing these classes. You have the agency to choose courses that aren’t too stressful.”

When deciding courses for the following year, students can benefit from considering whether they are sincerely interested in a class’s content.

“If you enjoy a course, like for me [with] AP Chemistry, that’s fine,” sophomore Ryeen Aghda. “If you have fun while doing it, it’s better than to just take an AP for the sake of taking an AP. I have friends who are taking three or four APs, but are taking a lot of engineering courses or history courses. I think they’re going to have an overall easier and more fun time.”

Student mindset also impacts ability to handle course load. Junior Ryan Park is currently taking AP Physics, AP US History, Linear Algebra, AI, and Computer Vision, all of which are AP or post-AP classes.

“Throughout this year, even though I don’t get the grades I want sometimes, just [because of] the effort I put in, I still feel satisfied with my grades,” Park said. “It’s not worth it to violate the honor code, because in the end you’ll only hurt yourself and the results will show later.”

On top of losing an opportunity to learn, students affect teachers by cheating in their classes.

“We need to have the teachers just say out loud to students what it feels like to be cheated on. I’ve had a few teachers who’ve gotten emotional during conferences when they’ve discovered a student cheating,” Burke said. “They feel personally hurt by the student not coming clean, and saying, ‘Hey, I’m not ready for this test,’ ‘I need another day in this paper,’ whatever it may be.”

Understanding the work a teacher puts into running their courses can also help reduce cheating in a class. During virtual learning, Owens had a list of statements every student had to acknowledge, ranging from, “I’m going to do my own work,” to “I recognize that Ms. Owens put a lot of time into writing this test,” to “I’m respecting her time and energy by giving my best effort on this test.” The most effective statement, Owens found, was making a student acknowledge “I am better than cheating,” before beginning the test.

“I [had] students tell me that it did make them think a little bit more about the human aspect of it,” Owens said. “Like, ‘What am I? What am I saying about myself? What am I saying about my teacher?’ That made them pause more than the Honor Code on its own.”

Future Consequences

When a student violates the Honor Code for the first time, their teacher fills out a referral. If the student admits wrongdoing, they meet with their teacher, counselor, grade-appropriate assistant principal, and parents. The student then faces additional disciplinary action or, alternatively, they can opt to work with the Honor Council.

“We guide them through [the] restorative justice circle process, in which the aim is not to punish the student, but rather try [and] get the student to understand why what they did was wrong, and for the student-teacher relationship to be repaired,” Bai said.

Restorative justice allows students to learn from their mistakes, rather than facing consequences like detention or suspension.

“It’s a much softer landing spot to come clean with your peers. I think to be able to say ‘I’m sorry,’ and for that teacher, the counselor, and everyone else to be like, ‘We accept that apology,’ wraps it up much nicer than, ‘Here’s your suspension or here’s your detention,’” Burke said. “I think it’s good, emotionally, to sit down with people [and] see how you’ve hurt them.”

Students are able to learn from their experience if they choose to cheat at Jefferson. But in college, students who cheat on assignments do not get second chances.

“It’d be interesting to have college students talking about it, because I don’t think our students understand how severe the penalty can be in college for this behavior. You can get kicked out of school or put on academic probation,” Owens said.

Those consequences are common in many universities, including the University of Virginia, an in-state university to which many Jefferson students apply; among 2022 alumni, at least 49 chose to attend the University of Virginia.

“UVA is single-sanction,” Hamblin said. “You cheat, you’re out. So we try to instill these ethics and standards in our students before they move on to college, where it’s less forgiving.”

Administrators hope to discourage cheating and promote a healthy mindset around learning, which students can carry with them after high school.

“We want to see a TJ which is not cheating,” Burke said, “and embracing the love of learning.”